|

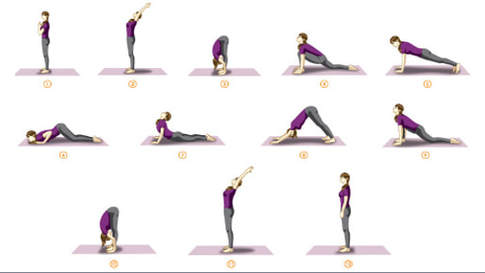

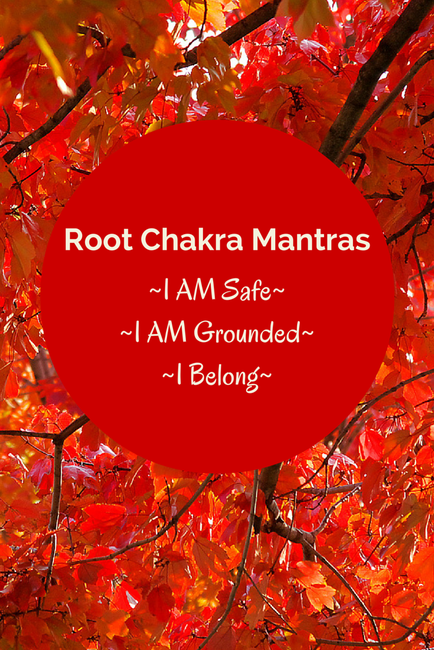

A week or so ago, a facebook friend crowd sourced the following question, “For those of you who've lost a loved one in the past and feel like you're healing… What habits, practices, or efforts have contributed to that healing? What should grieving people make sure they're doing? I responded with, “Do massage or yoga or energy work as often as you would do regular therapy. Trauma lives in the body in ways that typical talk therapy can’t get to.” Since Pete’s diagnosis with MS, I have been consistently curious about the mind/body connection. I use Louise Hayes Heal Your Body like a reference guide, easily acceptable to me on my kindle app. That led me to learning, practicing and teaching the Japanese healing technique, Reiki. I have used massage as a regular form of healing for myself. And recently, I’ve engaged in private yoga lessons with a skilled, loving Iyengar yoga instructor. Iyengar yoga is new to me. In the past, I have gravitated toward a flow practice, where my breath worked with my movement to find and release stress and discomfort. Iyengar seeks to perfect a post by building it from the bottom up. Staying in a pose and making microscopic changes has allowed me to explore my body more thoroughly. Last week, upon arrival to my yoga lesson, I explained to my teacher that during a massage the week before we were surprised at how “locked up” my sacrum was. Well, “surprised” is probably not accurate; it makes perfect sense. Our sacrum is at the base of our spine. Our spine holds us up, supports us all day, and all night. The sacrum is the beginning part of our root chakra. The root chakra is the portion of our body from our hips down to our feet. Energetically, or psychosomatically, our root chakra is all about grounding, being rooted in life. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise to either of us that my root chakra is “locked up.” With the death of Pete, my life has lost much of its footing. We cannot underestimate how much our primary relationships provide solid footing for us. Pete was the one at the end of the day who affirmed that I was deeply loved, despite whatever the day had brought. In a very real sense I have been uprooted and as a result my body is clinging to itself for stability. Physically, my muscles are locking onto themselves and affixing themselves to my spine. So my yoga instructor and I did a full hour of poses that would help release my sacrum. We started in seated position, stretching forward. We moved to side twists. We ended in down dog, finding that my hamstrings are connected to my gluts are connected to my sacrum. Yikes! Ouch! But here’s the thing, instead of loathing my body, being angry or frustrated that it was so locked up, I found myself in down dog, sending the thought, “I’m so grateful for you,” to my body. Maybe that sounds odd, but I am so deeply grateful for this body that continues to hold me upright. This body of mine is astounding. It is teaching me and supporting me. I am a body. I believe as a spiritual being that I am more than a body but for too long my spiritual life positioned my body against my spirit. As if my body was bad, evil, sinful. My spiritual life posited that it was its own being that could overcome, dominate the flesh part of me. Ultimately this is so unhelpful. My body is working really hard to help me be spiritually healthy. My spirit ought to be working really hard to make my body healthy. John Barnes, a renowned physical therapist says, “the body is not just a reflection of the personality, the body is the personality.” He also believes “the body remembers everything that ever happened to it.” I believe that too. At the point in my yoga lesson where I was thanking my body for helping me live my life, my yoga instructor asks, “do you know about fascia?”

Here’s what I’ve been learning since that question. Fascia is like the membrane of an orange and it’s all over our bodies. Fascia is made up of densely packed collagen fibers that wrap around each of our internal organs and connect them to our muscles and bones. Some like to imagine that perhaps we are not made up of 600 different muscles but instead we have one muscle that separates and distinguishes it into 600 different parts. Our fascia stabilizes our entire body and gives us our human form. It is a fluid system that literally holds all of our life together – and not just physically… Fascia contains sensory nerve endings. Proprioceptive sensory nerves help us perceive ourselves as separate from the outside world. Nociceptive sensory nerves help us perceive harmful substances like chili powder in our eyes or hot and cold temperatures. Interoceptive sensory nerves help us perceive pain and hunger. Our fascia not only holds my back together, it also holds all of the emotion that I have experienced since Pete’s death – the dread, the sadness, the fear, the relief, the gratitude, the delight, the want, the hope. It’s all there, in my fascia – in your fascia. John Barnes, renowned physical therapist says, “when one experiences physical trauma, emotional trauma, scarring or inflammation, the fascia loses its pliability. It becomes tight, restricted and a source of tension to the rest of the body.” So there is no amount of talk therapy that can get at the emotional memory locked in our beautiful, complex bodies. We are at our core, body. And I am lovingly helping my body loosen up its grip on life. Pete visited me again – this time it was after yoga class. I was sitting on my mat, the rest of the class had left. I was basking in the after glow of mindful movement. I was wondering how long they would let me stay in the space when all of a sudden he was in front of me, in the trademark Scibienski gargoyle squat. I looked up slightly as if to find his face and he said, “Hi cute girl.” A familiar greeting. “Hi,” I said. After a pause, I settled into his “presence,” I asked, “you ok?” A familiar question. It was the question I had asked so often for the past several years. Pete was so sick for so long. And as I settle into his absence, I am remembering how very sick he was this past year. I thought we had more time together but he was so very sick. And he needed so much of my attention and love and care. And our lives had become quite small, him and me and our greetings – hi cute girl and you ok? But that morning when I was settling into his presence, I had to imagine that the answer to “you ok?” is quite different than it had been. He was more than ok. He wasn’t sick anymore. He wasn’t wheeling through life anymore. He had full use of his legs and arms and he was squatting like he had done for most of his life. His answer came to me within his silence. His silence returned the question. “And you? You ok?” “I think I am. I’m not really sure what ok is. But I’ve started doing yoga again.” After a pause, I added, “And I miss you.” And again his silence spoke as if to say, “I miss you too.” and “I want more for you.” He misses me? Is that how this works? And he wants more for me? More what? Certainly not more grief. Maybe more than grief. More than the gnawing question of how I will do this without him. More than the constant struggle to breathe deeply. More than the confusion of how to live without him. Maybe those two thoughts go together. Maybe it’s not that he misses me wherever he is but that I am not myself. I am no longer who I was before he died. And I feel it. And I guess if Pete is real, he feels it too. He's right, I am not the same. And I miss me too. And although I wish I could hold a conversation without my mind drifting. Or hope to go into meetings without breaking down in tears, the missing myself is much deeper. I don't feel like myself. My body feels different all the time. My instincts are not the same. I am acting oddly for me. And it's truly intriguing that no one else seems to notice. In other words, I'm presenting fairly "normal." I suppose on the outside, I look the same, my relationships are the same, my job is the same, my voice is the same. I know I'm working to provide leadership and care as a pastor, and I'm doing so by relying on skill sets that I have honed over decades of ministry. But as I am living out each moment, I do not feel the same. You know what, Pete? I miss me too. He misses me and he wants more for me. But I don't want more. I want him. It all comes back to that. I want life with him. And he wants more for me. He wants me to find life without him. And so I said, “But I don’t want to do this without you.” When I looked up next, he was standing, waiting for me to get up off my mat. To take my practice into my day. To find myself and to find my more.

I’m reading Joyce Carol Oates’ A Widow’s Story. It’s scrumptious. In this retelling of her husband Ray’s sudden death, her writing is beautifully broken and raw. It’s not that she writes in fragments but her thoughts are short and contained. One thought at a time. One truth or one question or one observation. The story is told by a grieving brain. Don’t get me wrong – the book is still written by one of the most prolific narrative writers of our time. And while I’m no Joyce Carol Oates, my grieving brain has made a friend with her grieving brain. Grieving brain is odd. Grief affects many areas of our brain. I found this great article by Barbara Fane, that has helped me understand what is going on in my brain. For example, Our parasympathetic nervous system (in the brain stem anda lower part of our spinal cord) controls our autonomic nervous system – rest, breathing, digestion. When a person is grieving, breath can become short or shallow, appetite disappears or increases. And sleep can be disturbed; insomnia can be an issue. Our prefrontal cortex/frontal lobe holds the ability to find meaning, to plan, helps with self control and self expression. “Scientific brain scans show that loss, grief, and traumas can significantly impact your emotional and physical processes. Articulation and appropriate expression of feelings or desires may become difficult or exhausting.” The limbic system, the emotion-related brain region, particularly thte hippocampus portion “is in charge of personal recall, emotion and memory integration, attention and our ability to take interest in others.” While we are grieving, this area of our brain creates responses to loss and grief as a threat as a way to protect us from more pain. I can attest to my parasympathetic nervous system being fully functional. My breathing is shallow. My appetite is not what it used to be. I can’t finish sentences – and not like many of us who can’t find the right word sometimes. I am at a loss for words in regular speech so regularly that I’ve grown accustomed to speaking at a different cognitive level or being incredibly quiet in social settings. My vocabulary and syntax is decades below what they were before Pete died. As a pastor, I have feared I am not fully engaging with people in my congregation. Building relationships has always been the foundation for my ministry. But I’ve noticed that when others are telling me stories, I’m listening but not engaging the way I have for the whole of my adult life. Sometimes it feels like there is a me watching me listening to someone tell me a story. The best advice I’ve received is what would you say to someone if they came to you with these concerns? I would give them so much grace. I’d say, “Oh my word, you’re grieving your husband, your best friend. Your entire life is upside down. Of course you can’t breathe deeply! Of course you can’t finish sentences! You’re doing just fine. Be patient with yourself. Be kind.”

But now having gone through this, I would add, “your brain is doing the best it can and its even doing some of these things to help you. It’s good to remember that grief is a process of the mind and body.” I have worked so hard at controlling my thoughts, keeping my mind focused on what I think is best. But at the end of the day, I am a body. My body, specifically my brain, is working at Pete’s death. And I will choose to embrace my brain and its process. My brain misses Pete as much as my body. |

Books I'm currently reading:Archives

April 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed