|

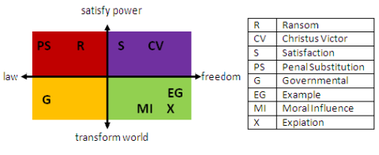

The text this week is Mark 12:1-12 I often start my online meandering of a text by looking for some graphic assistance, something to get my creativity flowing. This time I googled "don't kill the messenger." My music director and I were discussing the parable and his first thoughts were, "I don't think I get it." For starters, parables aren't supposed to be simple. And thinking metaphorically is not always easy. As a Presbyterian pastor, I have more people who uses their intellect more than intuition. They like concrete thinking that uses their senses and not their feelings. So parables can seem simplistic and then sometimes downright horrible. In fact, that's the next thing my music director said, "they seem horrible." Yes, the people who were leasing the land from the landowner are horrible people. It's something we would see from the Soprano's or Shameless.  I don't want to assume people understand parables, nor do I want to assume people don't. However, a little explanation in three different areas would be helpful. The Story: The farmers have been entrusted with the land to work it and produce fruit. After the allotted time, which may have been as long as three years for the land to develop and mature in its growing capacity, the owner comes back for some rent, a portion owed him. But he doesn't come back himself. He sent slaves, one after the other, each killed on the job. Finally, the owner still doesn't come back himself. Instead he sends his son.  Here's where the story gets truly insane. The owner thinks the farmers are going to treat his son differently than the slaves. It's a huge risk on the owner's part. And one poorly taken if we're honest. Unless his son is as expendable as the slaves. Allegory: Each piece in an allegory has meaning. vineyard = Israel fence= wine press= wine tower= owner=God farmers = leaders, scribes of the people share of produce= slave #1= slave #2= other slaves= son=Jesus  Moral Meaning: At this point, Jesus has predicted his death three times. This parable seems to be suggesting the reason why Jesus would die. He was coming to collect what was due to God. And like those who had gone before him, the slaves who worked for God, he too would be killed "on duty." Just like a note about basic allegory may be helpful, a little primer on "why Jesus had to die?" may also come in handy. Here's a website that seemed particularly user friendly. One thing I really enjoy about the Narrative Lectionary is that we start talking about the cross before Holy Week. Too often, when left to the high holy days of Maundy Thursday or Good Friday, theories about Jesus' death are lost in the need to reenact our faith stories. One more graphic that may be helpful giving a primer on "why Jesus had to die?" is here, a grid defined by satisfying power and transforming world by law and freedom. I'm going to spend a little time working up a one sentence definition for each of the theories mentioned in the grid. However, without explaining the various theories, I wonder where people would put their own "x" if asked what relationship Jesus' death had to the four areas on this graphic: satisfying power, transforming world, law and freedom. I wonder if our answers would reveal what kind of savior we want/need.

1 Comment

The text is Mark 10:17-31.  In this reading, we hear Jesus ask the same question twice. He asks, “What would you have me do for you?” In the context of just healing the blind man, who asks for his sight back. Which always begs the question when did he lose it? How long had he had it? How long had it been gone? This man's request is about now. He wants his sight back now . He wants to see (probably proverbially and physically.) And when I've preached the text of just Bartimaeus asking for his sight, this question seems appropriate to turn on us. If Jesus asked us, would we be able to answer? Would we want to answer? But when we hear the text in its entirety and realize that Jesus asked this same question earlier in the story to the two brothers who wanted to be on his “right and left” when he gets to glory. Really?! That's what they're thinking about. What will come of us when you are in power? What is going to happen to us... later? I, like the others, are indignant. What kind of request is that? Why did they need that? Why did they want that kind of security for what was to come? One asking for his sight back and the other two are asking for security in what is to come. Do we want Jesus' help now or are we concerned with later? Which is most common in prayers these days? Do we look to see what is or are we most concerned about seeing what will be?  I don't know that I'm willing to judge either request. Both can be subject to Jesus' call to serve and not be served. We're left without the final story in either case. We don't know how the brothers respond when told to serve rather than serve. We don't know how Bartimaeus lived his life after he regained his sight. We all have wants, needs. It seems the lesson that Jesus was teaching his followers as they walked themselves to Jerusalem was to serve. What do you think? What direction are you taking this text in your sermon? We at Grace Presbyterian are using posters from Illustrated Children's Ministry. to continue discussion in an intergenerational setting. And here's a download of a devotional to use for individuals or families. The text for Ash Wednesday in the Narrative Lectionary is Mark 9:30-37. As I read through the texts from the Narrative Lectionary for Lent 2016, I was initially tempted to call the journey, the "road to death." And then I thought that might not really get people to come to church so I read them again. Whether we like it or not, the Lenten journey ends with Jesus' death. And the road to his death leads to resurrection. It is the resurrection that contains our hope but the resurrection doesn't happen without death. So what then does Jesus' road to death have to do with us who will remain alive Good Friday? In what way is Jesus' journey to death meaningful for us as we embark on these forty days of Lent? How do we supposed to take the journey to death?

This first text begins with Jesus admitting what the road will include for him. He was telling his disciples that he would be betrayed and killed and then rose from the dead on the third day." He didn't hide the reality of the journey from his friends and he didn't ignore the realities himself. He welcomed what was to come.

It makes sense then that his first step on this Road to letting go would be to remind them what it looks like to welcome what God has brought into our lives. We are to welcome as if a little child. Come what may - Welcome with a warm embrace. Come what may - welcome as if it holds the future in its hands. Come what may - welcome with open arms. What will this road to letting go have for us? Whatever it is, might we welcome it! The first step to letting go is to welcome what is. Our text for Lent 1 from the Narrative Lectionary is Mark 10:17-31. Jesus says to the man, "sell what you have and come follow me." On this first Sunday of Lent, we begin with the notion that the things we possess are not as valuable as following Jesus empty handed. I'm looking at the weeks of Lent as various lessons along the way that lead to death, or that lead to letting go so that something else can resurrect. In this case, from this story, I hear "giving away" as an important lesson for letting go. Many people take on disciplines during Lent. I've "given up" a lot of things over the years - coffee, sugar, purchasing anything unnecessary. Yesterday I saw that our local library is having a book sale. What a perfect time to give away a portion of my library... not just the throw away stuff, maybe I should consider giving away that which would really "ouch." I mean the man in the story went away sad because he had so much. Well, I have so much too. I have in particular... so many books. We'll see what I come up with in my donation bag. How about you? What is it that you have so much of that you would rather go away sad than give it up? And I wonder if it's the letting go of the stuff that would make me sad or is it the state of being empty handed that would make me sad? Are we so full as a culture that we can't imagine being empty handed?

That's how Buddhists define emptiness. It's not a negative quality as if having too much and having to empty ourselves of it would make us walk away sad like the man in the story. But instead emptiness is a true quality of the human existence. The things we think fill us, or fill our spaces, or our homes or our landfills do not actually fill us. They are things to which we cling because they hide from us our true emptiness.

And the Buddhist would say clinging is the primary component in suffering. When we cease clinging - to the things we have, the items we own, the relationships we maintain, the life we breath, well then we actually begin living. The text for this week is Exodus 34:29-35 coupled with 2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2.  There is a lesser known book by C.S. Lewis entitled Til We Have Faces. It's one of my favorites. It is a retelling of myth of Cupid and Psyche from the perspective of Psyche's older sister, Orual. Orual suffers when her sister Psyche is sent away to Cupid. Psyche is forbidden to look upon the god's face but Orual persuades her to. Psyche is banished as a result of her attempting to see the god face to face. Orual is left to grow in power isolated from Psyche and any love here on earth. She spends her life wondering about the silence of the gods. A mentor of mine introduced me to this gem when I was talking about a book by Thomas Moore entitled, Care of the Soul. This book suggests we look deeply into our lives, removing any "veil" we might have in order to see the sacred in ordinary things. Although the two of these books seem dissimilar, they both dig for the true self - the self beneath the "veil." This is the self that Moses showed bare in the presence of God. When in front of God, Moses removed the "veil." Now in front of the rest of the people, he put on the veil. At present, in our culture, we seem to have little covering us in that our privacy is dwindling. Whether we're sharing our every move on social media or having our every move on the internet recorded by marketing experts, our lives are less and less private. But lacking privacy is not the same thing as having intimacy. When I imagine Moses standing before God face to face, I see intimacy. I hadn't really thought of this as a theme in my spiritual life but several books have come to mind indicating I have read and re-read others thoughts about how we might be, become or desire to be intimate with the Divine. Intimate Moments with the Savior - an accessible devotional book by Ken Gire who describes Jesus in beautiful storytelling and whose writing first made me want to write. Intimacy with the Almighty - a short 80 page treatise by Chuck Swindoll on slowing down long enough to be present with God, presence being essential in intimacy. Intimacy with God by Thomas Keating, an essential for anyone wanting to dive deep into centering prayer, Christian meditation. Developing Intimacy with God, a book that uses St. Ignatius of Loyola's Spiritual Exercises as a guide to becoming intimate with God. Intimacy with God is not sweet and satiating. Intimacy with God is a bold, dangerous endeavor. Intimacy with God requires that I know something of myself, that I have looked beneath my veil as Paul suggests in 2 Corinthians. In order for me to be intimate. I must first allow my veil to drop, to come as myself to God. Intimacy in any relationship requires time and dedication, listening and sharing, grace and acceptance. Moses was intimate with God. Do we dare to be intimate with God? In Til We Have Faces, the main character Orual realizes that she has spent her life beneath a veil and that if she was ever to have a real encounter with the gods, she would need to remove her veil. She says this, "why should [the gods] hear the babble that we think we mean? How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?”

It seems that the promise of transformation occurs when we are willing to have faces, to remove our veil. |

Search this blog for a specific text or story:

I am grateful for

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.