The whole congregation of the Israelites set out from Elim; and Israel came to the wilderness of Sin, which is between Elim and Sinai, on the fifteenth day of the second month after they had departed from the land of Egypt. The whole congregation of the Israelites complained against Moses and Aaron in the wilderness. The Israelites said to them, ‘If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots and ate our fill of bread; for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger.’ Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘I am going to rain bread from heaven for you, and each day the people shall go out and gather enough for that day. In that way I will test them, whether they will follow my instruction or not. On the sixth day, when they prepare what they bring in, it will be twice as much as they gather on other days.’ So Moses and Aaron said to all the Israelites, ‘In the evening you shall know that it was the Lord who brought you out of the land of Egypt, and in the morning you shall see the glory of the Lord, because he has heard your complaining against the Lord. For what are we, that you complain against us?’ And Moses said, ‘When the Lord gives you meat to eat in the evening and your fill of bread in the morning, because the Lord has heard the complaining that you utter against him—what are we? Your complaining is not against us but against the Lord.’  In the morning, when the layer of dew lifted, there was a flaky substance, as fine as frost on the ground. They did not know what it was. Right there, in front of their tents. Had they not noticed it before? Had they not woke early enough to see the dew evaporate? Was there a change of season happening - where dew would be more obvious? Or maybe the aphids (often called plant lice) had just migrated to the trees outside of the Israelites camp. Whatever the reason, they asked one another, "What is it?" From Wikipedia - Man is possibly cognate with the Arabic term man, meaning plant lice, with man hu thus meaning "this is plant lice",[15] which fits one widespread modern identification of manna, the crystallized honeydew of certain scale insects.[15][17] In the environment of a desert, such honeydew rapidly dries due to evaporation of its water content, becoming a sticky solid, and later turning whitish, yellowish, or brownish;[15] honeydew of this form is considered a delicacy in the Middle East, and is a good source of carbohydrates.[17] In particular, there is a scale insect that feeds on tamarisk, the Tamarisk manna scale (Trabutina mannipara), which is often considered to be the prime candidate for biblical manna.[18][19]  I tend to agree with this analysis. Manna = tree lice poop. What fascinates me then about this story is that their answer lay right in front of them. Every morning. Overlooked? Maybe. Arrived with a new season? Maybe. They complained for hunger and the next morning, right in front of them was an unknown substance that could be made into bread. It's not the bread they had in Egypt. But it was the bread they had for today, for this season of their lives together. And it was right in front of them, something within their grasp. I know myself and my own complaining. I would struggle to see that this flaky substance could be made into bread because it doesn't look like the flour we used in Egypt. I might fixate on not having bread like I know bread to be and not be able to see the gift of what I have in this flaky substance. Plan A is flour and oil for bread. I'm looking for God to provide Plan A. That's what I've prayed for - or complained about which is truer to this story. And since I want Plan A, someone has to show me that Plan B is what God has provided. Plan B is an unknown flaky substance that when ground and baked tastes like honey. Plan B, also known as God's answer to complaining, comes every morning. The thought of my affliction and my homelessness

0 Comments

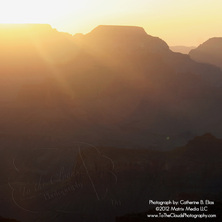

Exodus 2:23-25; 3:10-15; 4:10-17  You know the phrase, "you can never go home"? Moses has lived a lifetime away from Egypt when God calls him "home." Moses is a completely different person, a family of his own, a fully formed business of his own. He has built a life away from Egypt. He must've been asking, "Can I/ How can I leave this and go back to that place?" But none of that is in the text, none of the reason why Moses was where he was, none of the background with Pharaoh, none of the dual citizenship that Moses lived with in his heart. If we were to read these sections of the text on their own merit, we would see five characters:

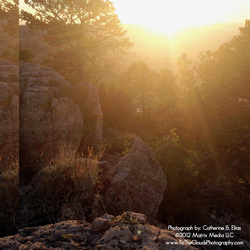

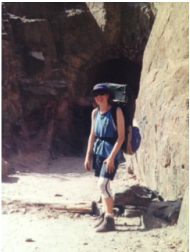

The bulk of the story is about Moses' reticence to go. I want to focus on this reluctant character, his fear, his backstory, his uncertainty, his inability to do that which God has asked him to do. I want to think about Moses' reunion with his distant brother Pharaoh or focus on Moses' relationship with Aaron, his other brother. It's a rich story made for the big screen, whether the classic "Ten Commandments" or the cartoon version "The Prince of Egypt." I'm drawn to Moses as the hero. But what of the people? And what of God? It is the people who initiate the story with their cries for liberation. And it is God who sets the story in motion by hearing their cries for liberation. The story is about liberation. The text that we have here is Act One, Scene One - in which God hears the people, calls Moses and employs Aaron to help.  I don't need to go onto Scene Two or Three just yet because I wonder if God is seeking to enter other stories of freedom in my world today. Is God hearing cries of others, cries for liberation, for redemption, for freedom? And if so, who is God calling, who is God employing to help those called? And what is the nature of the people's cries that have risen to God? Where is there slavery? Political? Social? Economical? Emotional? Physical? Financial? Racial? Domestic? It appears that God's intention is set. Moses does not appear to have the option to pass on his calling. Aaron isn't even in the conversation directly. And although I believe the story is about the people and about God's intent to liberate, I imagine the end of Scene One has Moses clinging heavily on his staff. After all, God has instructed him to bring it with him, this one piece of his current life, his chosen career, the symbol of who he has become. Genesis 28 ~ Then Isaac called Jacob and blessed him, and charged him, ‘You shall not marry one of the Canaanite women. Go at once to Paddan-aram to the house of Bethuel, your mother’s father; and take as wife from there one of the daughters of Laban, your mother’s brother. May God Almighty bless you and make you fruitful and numerous, that you may become a company of peoples. May he give to you the blessing of Abraham, to you and to your offspring with you, so that you may take possession of the land where you now live as an alien—land that God gave to Abraham.’ Thus Isaac sent Jacob away; and he went to Paddan-aram, to Laban son of Bethuel the Aramean, the brother of Rebekah, Jacob’s and Esau’s mother...  "Prints on the Sand" by Catherine Elias "Prints on the Sand" by Catherine Elias Jacob is on his way back to his grandfather Abraham's homeland. Currently they're living as aliens in the land that God swore to give to Abraham and his descendants. I wonder what life has been like for Isaac and then for Jacob - having arrived at the promised land but the promise has not yet been fulfilled. There's something about Jacob having to leave the promised land in order to find a worthy wife that won't let me go on. It's the promised land, right? But the inhabitants of the promised land are not worthy to mingle with. How long had Isaac had to live in isolation like this? And how did they raise their children in isolation like this? Jacob is a product of isolationism. Clear boundaries of where to play. Clear guidelines for learning. Clear rules for dinnertime. Clear expectations for taking a wife. It's not surprising then that Jacob would be surprised to find the presence of God somewhere he wasn't looking for it. He was after all, not with his family, not in their sacred home, not where he had always found God or experienced God. He was in a new place - a place where "others" reside. He and his family were strangers and they worshiped a strange God. How then was God in this other place? I was raised Baptist and Pentecostal. While a college student, I went looking for a church to call my own and I thought I would try something very different - an historic downtown Methodist church. The architecture was stunning, and vast with its grew stone walls and high peeked ceilings. I climbed the stairs to the balcony where I could have a bird's eye view, and maybe could hide lest someone find out I was an imposter, a stranger to this foreign land of Methodism. I saw people finding their seats, dressed impeccably. I saw a big Bible on the communion table and I saw a kneeling rail around the altar. Within moments, I could sense the presence of God in this place. I was stunned by it. How is God already here? We had not sung a song. We had not prayed a prayer. No one had said "Good morning" yet. We had not begun worship and yet God was clearly in this place. It seems so silly to me now but at the time I was so surprised to find a familiar God in a strange place. Genesis 21:1-3; 22:1-14  A coloring page - Really??? A coloring page - Really??? Let me put my cards on the table - I've been preaching weekly for 8 years and I've never preached this text. Another card I've got is - I've been pastoring for 20 years and I have had dozens of conversations about this text with folks. This text is absurd at best; it's disturbing and unconscionable at worst. What kind of God tests someone by asking for a human father to sacrifice his only son? What kind of horrific father was Abraham anyway? And Isaac? What became of him after this psychologically damaging event in his life? And don't get me started about Sarah. Where was she? We're still reading, interpreting and commenting on this text as if the literal story must teach us a moral lesson. We're still reading, interpreting and commenting on this text as if the presenting story teaches us something about God, about humans, about family values. The only sermons I've ever heard about this text leave us with the obvious Christian theological lesson - Abraham sacrificing Isaac is a foretelling of God sacrificing Jesus. I can't preach it this way for two reasons. First, I typically honor the Hebrew scriptures by keeping them true to themselves without inserting the Christian scriptures and their meaning. Second, I have a problem with violent atonement. The idea that God would require a human sacrifice is - foul. When Abraham had the thought that God wanted him to sacrifice his son, why didn't he recognize it as foul? And when Sarah heard about it, why didn't she tell someone that her husband had gone mad. And then why didn't she pack her and Isaac's bags and run away? When Isaac realized his dad was going to do him harm, why didn't he overpower his father and since he didn't, can we assume that he'd been abused by his father for so long that he had lost his voice? If you're still reading - you may be quite irritated by my lack of respect to the patriarch. I'm asking these questions because I find them to be lacking in the discussion. Instead of shaking our head in disgust and picking at the text in the critical manner we usually do, we approach the text with our preconceived notions. We have already decided that God is good and it taints our ability to see this text for what it is. Abraham is our patriarch; he too must have been a faithful person (after all Hebrews 11 says so). As a result, we overlook reasonable perspectives of this hideous story. We have already accepted that women and children have no say and so we perpetuate the hidden, abused, ignored, discarded voices in the scriptures. When you read this story, whose voice are you listening to? In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light. And God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness. God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, the first day. And God said, ‘Let there be a dome in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.’ So God made the dome and separated the waters that were under the dome from the waters that were above the dome. And it was so. God called the dome Sky. And there was evening and there was morning, the second day.  the trail down the canyon the trail down the canyon The Generations of the heavens and the earth... Not the generations of the patriarchs or matriarchs. Not the generations of the descendants of Adam... or David... or Jesus... or the people of God. The Generations of the heavens and the earth. Before my final year of college, my best buddy and I traveled the southwest and received Earth Science credit for doing so. There were less than 20 of us in the class with three or four professors. We traveled by vans from Oklahoma to Utah for 26 days, stopping at Mesa Verde, the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest, Zion National Park, the Grand Canyon and Bryce Canyon. Each day we set out to explore and each night we set up our pop tent to camp under the stars. This was my first encounter with the generations of the heavens and the earth. When we hiked into the grand canyon, we hugged the walls of the earth closely. My left hand caressed generations of earth, layer upon layer upon layer of rock formations. Kaibab Limestone at the top followed by the Toroweap Formation. Coconino Sandstone too. One of our assignments for this course was to memorize the layers of the canyon. We made a song about it to the tune of Rudolf the Red Nosed Reindeer. Generations of earth, piled upon one another, years of formation, rain storms and sunrises, snow storms and sunsets. Wind and glaciers. Generations of the earth. What you see from the top of the canyon is not what you see from inside.  My buddy Janean My buddy Janean This text, the first of the creation narratives (remembering of course that there are two creation stories in the scriptures, the other is in Genesis 2.) This first one is poetic in its repetition. I can hear it as liturgy. The wind of God is the leader in this worship setting. Those of us encountering creation are the participants. I can hear the wind beginning each verse, "And God said..." And we respond, "And God saw it was good." And the wind says, "And there was morning and there was evening..." Our days, the earth's days, the generations of the heavens are marked by the wind of God, sweeping above and below, before and beyond us. Creating, fashioning, forming layers upon layers. The patience of God, the persistence, the constancy amidst a changing landscape. These are the generations of the heavens and the earth. |

Search this blog for a specific text or story:

I am grateful for

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.