I was asked this question recently - Does God cause or allow illness? If so, why do we pray for healing? I thought I'd share my answer here.  Sickness is part of the human condition. We are incredibly fragile. We bruise and bleed fairly easily. But here's the thing, we also heal proportionately, fairly easily. We break bones and even contract diseases like cancer or multiple sclerosis and with the help of others and the gift of medicine or treatment, our bodies find ways to live through and often with illness. When I hear someone asking does God cause sickness and if so, why should I pray, I hear the question more about a cognitive change of what we think God is supposed to do or be. Make sense? We think God is supposed to do something or be something. And then God doesn't do what we thought or isn't acting as we thought. We think God has changed – but perhaps maybe it's us who needs to adjust who or what we thought God is. If God isn't what you thought God was, then go find out what God is. And most importantly, just because God isn't what you thought God was, that doesn't mean that there is no God or that God doesn't care. It just means we need a better definition. So how do we find the better definition? Prayer. Prayer is our way of being with God. If you needed to understand your friend better, what would you do? You would spend more time – listening, exploring, watching. The frailty of our human condition continually pushes us to adjust our definition of God. That's good. Don't walk away from faith, lean into it.

1 Comment

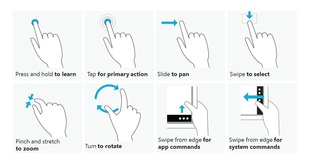

Is this 21st century touch? Is this 21st century touch? The receiving line at church is like speed dating but pastoral care. It's speed pastoral care. I shake hands, hug and/or smile to 60 consecutive people, all carrying their lives with them. Most of the time it's a ministry of touch. Did you know that for some people the only time they are touched is during church on Sunday either at the passing of the peace or in the receiving line after service? Each person comes through the line, smiling at me, greeting me and waiting for me to smile and greet them. We touch. Hand to hand. Cheek to cheek. Shoulder to shoulder. Face to face. I have mere seconds to look into their eyes for clues or emotion. Mere seconds to remember that they asked for prayers for their mother or that they have a procedure pending or a sister about to have a baby. Mere seconds to connect the knowledge that I have of them to the touch that I'm about to give to them. Most of the time it's just needed or wanted touch. Touch. We don't touch a lot in our culture. Honestly, we don't. And we're getting less and less the more we have to regulate touch in public places. This article says that one of the growing professions over the next decade will be the massage therapist. That's not surprising – in a world in need of touch with rarer and rarer opportunities for touch, enter the massage therapist. But not all massage therapists are equal. Take mine for example - I was talking to her about some new clients that she has. She's expanded her practice to offer some appointments at the new Wellness Center in town. Her clients presented with a variety of illness or issues. She loves a hard case. She loves to work toward healing and wholeness in people's lives. Not all massage therapists are like that. I won't name names but we all know the places that offer memberships – well, that's not the same kind of massage as going to someone who has taken care to further their education in the healing arts. Not all massage therapists are equal. What I look for in a massage therapist:

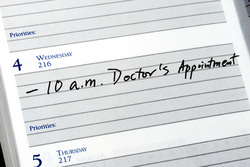

I love having lunch with Mary Ellen. We begin with cheese, crackers, veggies and dip while we kibitz about our lives. Mary Ellen was on the search committee that called me to the church. She is a retired English teach from the same high school that I attended. (I'm so grateful that I never had her as a teacher; I was a serious underachiever in my youth.) She sports a stylish short, platinum blonde haircut and she wears sandals well before Easter and well into the fall. She's been an elder for most of my time as a pastor, re-vamping the Outreach Team and working toward more encounters with hurting, broken people in the world. I'm deeply grateful for her skill set, her honesty, her heart and her ministry. After the cheese and crackers, she whips up her usual Caesar salad with shrimp. I hardly ever eat fish because Pete is allergic. She knows this and that's why she always makes me shrimp. She says a prayer for the meal, giving thanks for friendship and for lengthy lunches together. Amen. Mary Ellen knows loss. She is acquainted with sadness. I would even call her an expert on grief. She has buried three husbands and two best friends. She lost her mother to Alzheimer’s. She has also quilted together an incredible family from the broken pieces of three families. She loves them; and they love her. She is grandma in her own unique way while always honoring the other grandmothers involved. When Mary Ellen cries, her tears come in every color of grief. I have learned to stop dead in my tracks when she begins to cry. Her tears have shown me colors of the rainbow I did not know existed. One of her best friends that she watched die was also a member of my congregation, Jean. Jean was diagnosed with ALS. While Jean suffered, I often found myself at Mary Ellen's lunch table sharing wine and sadness. “Mary Ellen, how are you doing with Jean?” She gathers tears in her eyes, finds a tissue and says, “I don't know why I bother with mascara anymore.” After a pause and bite of shrimp, she tries to start again, “It's hard, it's really hard. She's suffered already with the breast cancer.” Sniffing, she finds her forceful voice to say, “And she fought hard, she won and look at this now. I can't bear to see her suffer like this.” I finish chewing and say, “How can I help you through this?” This afternoon, she began talking about her mother and the awful disease of Alzheimer's. “I thought it was the worst, until this happened to Jean. This must be the worst diagnosis.” She continues with, “I don't ever want to go through this. And I won't. I don't think I've told you this yet but I'm going to take my life if I ever get Alzheimer's disease.” Looking up from my salad I say, “I'm sorry; what?” “I might as well tell you now, Jean and I have spoken about suicide at length. We've even purchased this book. I will lend it to you when I finish. It's all about how to kill yourself. And did you know that none of the options are ever really secure. The author suggests that you always put a bag over your head just in case your first choice doesn't work.” I take a deep breath, put a smile on my face, pour another glass of wine and say, “Stop, just for a second.” She laughs with her wonderful chuckle, shaking her head at this youngster pastor who she has grown to love and need. “Start over. Jean wants to kill herself?” “Well, we've talked about it but I don't think she'll be able to do it. She's always been such a good, Christian girl. But we've been looking into which pills she is taking and how she could collect some on the side. The thing that makes me most mad is that there isn't assisted suicide in NJ. I told Jean, 'I love you but I'm not going to jail. You're going to have to do this on your own. I'll be there with you but I can't help you do it.” “What does Jean say to that? I ask. “She agrees and also laments that there is no assisted suicide in NJ. If there was, this would not be an issue. She would be able to talk to her physician about her wishes. The problem with ALS is that by the time it's too much for her to handle she won't be able to do it herself. She'll be too weak or she'll have lost the use of her arms or even her voice.” We pause and look at one another. Who gets to have these conversations in our culture? Clearly doctors don't. Families may. And if they're lucky – pastors get to have these conversations. My training would tell me that thoughts of suicide are signs of disease, severe signs of an unhealthy human being and that this conversation needs to be shared with a professional. After a second consideration, I realize that I am the professional with whom it is being shared. Don't get me wrong, I don't have delusions of grandeur and I “refer, refer, refer” all the time. This conversation was meant for her pastor; I am her pastor. So in all of my inexperience, I respond with these words, “well, I don't think that any of this should happen alone. I don't think anyone should die alone and I certainly don't think any of us should go to jail for helping someone die.” I don't know exactly what that's going to mean practically for Jean or for you. But when the day comes, if the day comes, I want to be there. I think your pastor should be there.” Jean wasn't able to take pills to end her life. Instead, she entered hospice care where a nurse administered doses of morphine. Mary Ellen laid beside her on the hospital bed. Along with others, I sat beside them. For now, the book about how to kill yourself is on a shelf.  I recently discovered Twenty Two Prayer Poems for Caregivers by Donna Iona Drozda. I commend it as a great gift for a caregiver. This prayer in particular has been meaningful for me lately. Harmony and Harmlessness I pledge to do no harm. Dear One, It feels as though I need to protect myself. It feels as though I am being attacked. Wherever I go at this time it feels as though I am an outsider. I am bereft at hope and I fear that all of my attempts to Learn to walk in balance are for naught. I look about me and try as I may to see the beauty May eyes seem magnetized To the pain and suffering and ugliness. Humbly I ask that You Give me new eyes in this moment. Remind me that this world is all an illusion Remind me that nothing real can be threatened. Teach me to forgive the world. Teach me to forgive myself. Show me how to correct my thinking. Bring me back to balance. I am willing to step back today and let You lead the way. I am willing to be taught... There is another way of looking at the world. I am willing to give over my fear. Again and again throughout this day I will be still an instant and go home. I will listen to Your gentle guiding voice. Amen.  Sunset over the bay, Ocean Beach, NJ Christians believe in the resurrection. I had a friend, Dave, who died after a battle with brain cancer. A few of us were sitting around discussing the biblical story about Jesus coming back from the dead. In this story, he shows up while his friends were having a meal. They don't recognize him until he did something familiar (in this case he broke bread around the table.) Then the scriptures say that their "eyes were opened and they recognized him." (Luke 24) As we were talking about the text, someone asked, "What would we do if Dave walked in the room right now?" I've never forgotten that question. What would I do if someone I loved came back from the dead? I'd freak out. How about you? Christians believe in resurrection. I have a friend who served a very small church with a declining membership. They were a farming community. But instead of corn, those fields are filled with homes. And those homes are filled with families who who commute to work and spent their Sundays at soccer games. In the last 20 years, there had tried programs hoping to resuscitate the life that they had known. There was even a suggestion that they reintroduce the spaghetti dinners to raise enough funds to pay their bills. My friend offered what I believe was a prophetic word when she said, "Christians don't believe in resuscitation; we believe in resurrection. And in order for something to resurrect, something must first die." While I was a chaplain, I watched a group of doctors resuscitate an elderly gentleman. Resuscitation is a gruesome act. It often involves broken bones and blood. While physicians were desperate to monitor blood pressure and breathing, I was monitoring family, vulnerability and impending grief. Everyone in the room wanted to save life. I wanted death. Resuscitation is about holding onto the life we have. We hold onto, we cling to our lives – exposing it sometimes to gruesome acts just to keep what we know. We try all kinds of things to resuscitate the life that we know. “If I do this, we can keep this.” “If I accept this, then we can stay here.” “If we adjust this or that, then this or that will stay safe.” We fight death; we fight loss. We ward off death; we resuscitate. Living with chronic illness is about managing mini-deaths. When Pete and I can no longer do certain things or go certain places, the adjustments that we have made often seem like small acts of resuscitation. Why? I cling. I cling to the life we had. I cling to the dreams we dreamed together. I cling to the life I thought I would have. But when a dream is dying, or MS has taken Pete's ability to walk, I'm wondering what would happen if I had the courage to say, “do not resuscitate?” Do not resuscitate that dream. Let it die. Wait for resurrection. I know what happens if I don't let dreams die. I wake up each day proverbially breaking bones and cleaning up the blood from another round of resuscitation. Exhausted and spent – still living with the half life that I won't let go of. Christians believe in resurrection.  My chaplaincy was spent at a “trauma 1” center. I watched summer nights yield knife fights and gunfire. I caught a burly, tatoo'ed man in my arms as his wife was wheeled into the ER. She lost control of her motorcycle while trying to avoid a truck. I sat with a widow whose husband fell off a ladder affixing Christmas lights. The definition of trauma is any situation or event that distresses or disrupts. In other words, if we are traveling one way and something stops us in our tracks – that's trauma. I hit someone; I stop them from whatever they were doing – that's trauma. Trauma doesn't necessarily have to be a damaging physical event but usually our physical bodies are involved. But the trauma that continues to inform much of my understanding of our ability to control life happened when two teenagers made a suicide pact. My beeper went off – Code 40, Trauma, 5 minutes by ambulance. One boy, dead on arrival. I never saw him or his family. But his friends were surrounded by dozens of hands, each in control of one portion of this young man's treatment. The chaplain reports to a trauma call. I typically stood right outside the room and the door was often left open. I held the space as sacred – I whispered prayers. I watched; I breathed. In a frenzy of doing everything within our power, I represented what is beyond our power.  I wasn't alone outside the room. Other physicians waited their turn, patient advocates looked for contact information while security guards cataloged the patient's belongings. The guard found a note, began reading it and looked up – his eyes searched for me. “Are you the chaplain?” “mh hm,” shaking my head. He handed me the paper. I began to read a scratched out note that laid clear intentions of a suicide pact. I took a deep breath,looked up from the note to find four physicians standing over my shoulders reading the note. I touched them lightly on the shoulder, the arm, “Hey, you ok?” At first they didn't say anything. They didn't want to look at me. As the chaplain, I represent all of the things that are out of their control. Again doctors and nurses are trained to do everything in their power to heal. My presence reminds them that not everything is within our power. And when trauma happens, we find so little within our control. I tried to get their attention again, “Seriously, everyone, how are we doing?” One finally spoke, “It pisses me off.” Another spoke up, “Stupid kid, he writes the damn note and he survives while his friend dies. What's he gonna do now?” “He wanted to die. Look at all that's going on to save him right now.” Our eyes glanced up to see all of those hands working diligently in the trauma room. Before you think “doctor's aren't supposed to talk like that,” I want to make sure I say I learned about courage and diligence from hospital physicians. I learned to do the job in front of me, with all that I've got until my shift is up. Then I learned to trust your colleagues to take over for you. I learned to take small breaks in between crisis. After talking through frustration and making sure they were heard, I folded the note and handed it back to the officer on duty. With a sad smile, I asked the patient advocate to call me when the young man's parents arrive. I found a seat in the hotel lobby where there is a water fountain and a gas fireplace. I caught my breath and tried to imagine this family's next 48 hours. I whispered prayers and cultivated a spirit of peace and acceptance, preparing myself to look into the eyes of his parents. A couple hours later, after the psychologists and social workers had seen the parents, I knocked on the door, both parents stood beside the bed, a physician checking his vitals. I'm Beth, I was the chaplain on call when your son arrived. “Did you see the note? I nodded. “Did you?” I asked. “Yes.” And after a pause, she said, “We don't understand.” “I imagine you wouldn't.” Tears were dripping on her cheek forming a continual streak her right cheek while her left eye was being blotted with a tissue. After a period of silence together, holding the sacredness of this space,I touched her shoulder and said, “Be kind to yourself.” He was to be moved to a facility soon. I told her that she would remain in my prayers – for strength and wisdom and that she would extend kindness to herself. I packed my stuff and prepared to leave my shift, passing on information to the next chaplain on call. I remember the drive home. It was not quite gray. The sun shone through the wispy clouds here and there. There was a slight breeze. I watched as the world began to wake up – a woman walking on the sidewalk, a guy putting out a rack of shirts at a storefront. When I arrived home, I made coffee and found a place on the couch to stare out the window for awhile. What just happened? A person tried to take his own life; a person was unsuccessful in trying to take his own life. Unlike the majority of the people who enter the emergency room by ambulance, this one didn't want to be saved. He had planned for death. He had tried to take control and failed. It would take me another 3 months to realize that my struggle with this specific instance was about “control” and our lack of it. As a chaplain and as a pastor, I have developed a relationship with the fragility of life, the randomness of illness, the frightening reality of the world around us. But those things happen to us and we have no control. This young man had tried to take control – and even that was out of his control.  Most people go to the doctor once/year. For those dealing with chronic illnesses, doctors are practically part of our families. Our doctors know our weekly activities; they remember our kid's names. Take for example, our chiropractors... Dr. Mike and Dr. Heidi. I've gone to the chiropractor my whole life, not Pete. In the 2nd year of his diagnosis, he gave it a try. I'll never forget the first adjustment for him – he slept through the night. He couldn't remember the last time that happened. Sleeping for the chronically ill is currency. We assume with MS that his neurons have fired five times in order to make a complete circuit making it possible to do a simple task like move his right leg. Sleep is his friend. Sleep generates more energy. Sleep provides a reboot to his system. A full night of sleep = priceless. He goes to the chiropractor every week. I go every other. As a caregiver, I experience some stress... but still – every other week? Is that necessary? Physically – I'm not sure. Emotionally – without a doubt – completely necessary for me. It's one of the only times during my week where someone else cares for me. They look me in the eye and ask how I'm doing. They touch me, lovingly as a physician and companion on life's journey. They know a portion of my life better than anyone else. And they hold that knowledge in trust. One week, Pete was having a particularly bad week. He stumbled as he entered the waiting room. Dr. Mike took over. He helped Pete up. He got Pete started with treatment and then motioned to me to follow him. We were headed into their back coffee room. Having never been in there, I took in the sights of their personal space – nothing more than a closet really with a coffee maker, some mugs and a place for their stuff. I looked back at Mike and he asked, “How are you?” fully expecting an honest answer from me. I started to say “this kind of thing happens all the time. Pete gets tired. This has been a bad week. And he interrupted me and asked again, “but how are you?” I had been holding back tears probably for three days but here they come – I was determined to at least control the pace they would fall. While I was attempting to control my tears, he told me about his experiences with his dad who has parkinson's. He used words like frustrated, disappointed, exhausted. He asked if I was taking care of myself. While I appreciate this question, I often feel judged by it. If my answer is yes then I suppose that means that whoever asked thinks I look horrible or run down. If my answer is no, it's because I can't find the energy or time and then I feel like a failure. And yet when people ask, I'm am reminded that others think me caring for myself is important. That's nice. Truly. But a better question might be, “How can I offer you care? Not Pete – you?” So Mike asks, “Are you taking care of yourself?” I say, “Yes, I exercise, I do yoga, I read, I write, I cook. I have friends and... I come to the chiropractor.” He smiled and waved me out of the coffee room and into a treatment room saying, “Let's get at that then.” Lying face down on the table, I judiciously allowed my tears to leak out while Mike massaged knots out of my back and straightened me out again. Having cared for me, he grabbed my hands and lifted me back into my life as a caregiver. This is one of the pieces from my sabbatical, an intentional period of time that I took to reflect and write about experiences of providing and receiving care in my personal life and professional life.  Caregiving. What does that mean? I mean really – what does it mean? I give care? Like a present on a birthday. Here you go, open it – it's “care.” I care. No need to say what I care about. It may not even be you. I care. In other words, I no longer say I don't care. A friend of mine was told that she doesn't care by her 10 year old son. What? What do you mean I don't care. Well, mom – you always say - “go ahead, I don't care.” What? Of course I care, she said. But his reasoning was sound. She did often say she did not care. Can I go to the neighbor's to play? I don't care. What do you want for dinner? I don't care. Mom, can I bring this to school? I don't care. What should I have for snack? I don't care. Coke or Pepsi? I don't care. And yet here is a gift, wrapped for you in colorful pastels. There is no bow however. - I couldn't find a bow. And no need for a card because I didn't think you would care. Go ahead – open it. And as I smile watching you you rip at the colors to find a box of “care.” Thank you. You care. Yes, I do. No, it is not that.  Caregiving. What does that mean? I mean really – what does it mean? I give care? I give care, offering it up like I do with my weekly offering in church. The plate is passed and I reach into my wallet, leafing through to find that there is indeed cash in a cashless society. I count out an appropriate amount and fold it as to hide my amount of giving. When the plate is passed, I overt my eyes to the usher but smile nonetheless when I give my care, grasping the plate and pass it to my left, again averting my eyes yet smiling. I look down at my knees and then come back to reality the piano is playing a haunting tune. Why haunting? Why play something haunting while we are giving our cares? Unless the music is taking them away. I cast all my cares upon you. I lay all of my burdens down at your feet. And anytime I don't know what to do, I will cast all my cares upon you. Caregiving, carecasting... Ah... it means casting care like a fly fisherman. A long line with colorful plastic feathers at one end, attached to a hook. Switch, switch, switch – the line floats over head and with the flick of my wrist, I cast – switch. The feathery hook barely touches the water – luring the fish to the service with one question, “What was that?” Looks like lunch. Casting care. Care giving. A rhythmic flow of the thin, barely noticeable line moving to and fro – arching and falling like a giant bubble, like the ones we hope to create while playing outside with our children. Blowing bubbles, casting lines, casting care, caregiving.  Small blue plastic container labeled “bubble magic.” complete with a tiny plastic magnifying glass looking tool. Lift it out to discover it is not made of glass at all. - it is filled with soap. Soap that when blown through will make bubbles. Lots of tiny bubbles. Sometimes streams of them. Sometimes one big large one – if blown with patience and intention. Stream of constant air pressure, the same pressure, the right pressure – don't stop, if you do it will pop. The bubble is growing and growing and growing and then it pops. Dip again, try again. Bubbles, lots of tiny bubbles. All around, go collect them, catch them. Watch them wash your arms and legs, one round spot at a time. Giggles, playing, life is good. When someone cares enough to blow bubbles for us to catch. I care. I give care. Yes, I give to another. But my motivation is still mine. I cast care like a feathery hook, I try to make right with the same patient intention with which I attempt big bubbles. Slowly, slowly, with consistent pressure. Until it pops. It always pops. Dip again, try again. Cast again – lure the fish to the surface with your feathery hook. Caring – for my own want for fixing. If I cast right, If I make the big bubble, then my care will work its way to a better life for me as well as the recipient of the gift of care. It is not a present just for you. This is one of the pieces from my sabbatical, an intentional period of time that I took to reflect and write about experiences of providing and receiving care in my personal life and professional life.  My earliest memory of community life is Sunday school at Stelton Baptist Church. I'm not sure how old I was. But what I remember was that I was sitting at a table with a handful of others beside a window that let the fall sunlight in. There was an activity at the table but what I remember was that we were talking to one another. The raw ingredients are: a table, conversation, and "others." I spend my life trying to reproduce that memory. As the pastor of a church, as a mother, as a friend, as a colleague, as a wife - I try to reproduce moments where people gather around a table to talk with "others." It's easy to gather with people "like" me but forced community - intentional community with people that are different or with people that I do not know well changes me for the better. It's why I am a church person. Every week I gather with people who have certain things in common while at the same time span a variety of ages, genders, interests, abilities and needs. As a caregiver, I have longed for a community similar to the one that I find in church. Pete and I have wandered into a few MS support groups with hopes to find people who have the commonality of the same disease while at the same time can offer us a variety of ways to see that same disease. We have not found that group yet. Our first attempt at a support group went horribly. We drove to the East Brunswick public library - nervous, scared, and generally stressed-out - only to find that the group wasn't there. We were lost and so were the folks at the front desk. The amount of anxiety produced by this experience created tears and disappointment - the kind that are only subsided with fried food or cheesecake. We opted for both. I want a support group. Pete probably needs one, but hasn't asked for this himself. I am persistent and so we tried the same group again. This time I called first only to find that it was December and they were having a holiday party and this probably wasn't the best month to start coming. We tried again. This time, for some reason, the group had been assigned a different room that evening. The room was not conducive for folks with wheelchairs and scooters. The "leaders" of the group were visibly flustered by the change of environment. The air was buzzing with that frustration and my own anxiety level was not enjoying this experience. Although the group had said that all are welcome: those with MS and support persons, I was the only caregiver in the room. If you're a caregiver and you're in a room filled with folks who need help. Forget that... if you're human and you're in a room with a bunch of people who clearly need help... you help. And so I helped. I helped folks find a place at the table; I helped folks get around the room. I smiled; I poured soda. I held back tears. This time we did not drown my tears in fried food or cheesecake. We just went home and went to bed. We tried another support group - it was at a Presbyterian church. I thought I'd feel more at home in the environment, which I did. But I still was the only support person present. Pete enjoyed this group more because there was a speaker and a time for Q&A. It's interesting that he has more of a need for information than for connection. I have more of a need for connection than information. Some have suggested that I try a general "caregiver" support group. I haven't done that yet for a couple reasons. When I ask about the demographics of the groups that some have suggested I find that those groups are filled with two types of caregivers: those caring for their parents and those caring for a spouse with dementia. At this point of my search I began to wonder if I'm looking for something that I might already have. The other day, I was sitting in a restaurant with three women from church. We had met in Princeton to support a friend who had moved her husband into a long term facility. He has severe dementia. I have journeyed with her as she made this difficult decision. She and I were joined by a woman who has recently found a 2nd love in her life after having lost her husband to cancer many years ago. She's beaming - all the time. The fourth seat at the table is taken by a woman my age with two teenage sons. We settled into a corner table, surrounded by windows that let in the sunshine. A table of "others" - each with their ages, genders, abilities, interests, and needs. We each bring our perspectives, our hopes, our losses, our sadness, and our longing for "other." These people in my life make me a better person. They make me think. They look at me when I'm talking and their eyes say, "I am happy to share life with you." I don't mean to be legalistic with this suggestion but life in community is better than life without it. I still hope to find some room of caregivers to spouses with MS. But in the meantime, I am deeply grateful for the community of others that I already have. I am grateful for others who sit a table with me beside the window that lets in the fall sunshine This reflection was written over my summer sabbatical. I share it this week in memory of a beloved congregation. I watched a movie this week that reminded me of her. I saw her niece last week. And I'm going to the theater tomorrow with one of her closest friends. When we choose community, we experience life exponentially - the good and the bad, the happy and the sad. Pete electric wheelchair is a hand-me-down from Jean. We remain so very grateful for her life.  A woman on the committee that interviewed me for my current pastoral position was assigned the task of asking me a few questions on behalf of the committee. In the conversation, we got talking about my studies in seminary; she was a classics major in undergrad who went on to teach middle school students. She was retired at this point, enjoyed reading and gardening. She had two large, grey poodles who I would later find out were trained as therapy dogs. The older was a bit better at visiting people in the hospital; she was more docile in nature. But the younger, rambunctious one brought the livelihood that many in the nursing home enjoyed. Jean was a breast cancer survivor who found many ways to “give back.” The decision to train her dogs as therapy dogs was one way that she could serve people who were in pain. She was not afraid of pain. She mentored other women going through treatment and she spoke at cancer groups. The first thing I noticed about Jean was her speech pattern. She spoke intentionally with a little rasp in her voice, slowly – very slowly, like she had a hard time getting the words out. Listening in general takes patience so with Jean, we found a tad bit more patience. Jean was a church person. Her parents raised her in the Baptist tradition and she knew her way around the Bible really well. But with her knowledge of the classics, she also knew her way around mythology and world religions. She was the leader of one of the small groups at our church. An interesting group of people who followed the thread of their interests, finding resources along the way. Jean and I spoke often about our theological journeys – how did we go from memorizing bible verses to understanding the Bible as the stories of the faithful as they sought to understand God. Jean and her husband Charlie sat to my right about 7 pews back on the side aisle in church. Always ready to worship, always quick to encourage, and always ready to “help out.” She had served as an elder for years, specifically functioning as the clerk of session (the Presbyterian position on the board of elders who keeps the minutes and keeps the sanity.) She'd served a variety of committees, mostly the mission committee as she was deeply committed to social justice concerns. She and her best friend Mary Ellen were responsible for the Heifer International Booth at the Mission Fair each year. Decorating the booth with farm dolls and replicas of barns, they wore themselves out talking about the gift of a goat or how a few chickens could sustain a family for generations. While Jean was committed to brokenness around the world, she found herself drawn to conversations with people in her immediate sphere of influence – conversations about our personal brokenness. And the church – well, that church has its share of personal pain. So Jean was invited to serve as a Deacon right around the time that I invited the Deacons to begin having a conversation about pastoral care. Many times, the Deacons of churches end up taking on all kinds of “helping” ministries: they organize taping the service, or arranging for chancel flowers or take care of fellowship time. Those ministries are needed, but Jean was asking for more, “How can we be more intentional about providing pastoral care to those in our congregation who are hurting, who are broken?” And thus began our journey from a deacon board who “helped out” to one who befriended others. Jean was a strong leader, some might say strong headed. And yet she couldn't have weighed 120 pounds. She was almost feeble looking, until she shared her opinion of course. She had short, salt and pepper hair that was always styled. She enjoyed make up and jewelry and so a pair of faded jeans, were paired with a yellow and blue long sleeved cotton top was matched with a chunky silver necklace and matching earrings. She wore glasses and had caring, serious, blue eyes decorated with a tasteful amount of mascara and eye liner.  She set about in her own style to rework the board of Deacons, organizing the “families” in the church so as to provide optimal care. She began to distribute the more painful situations: an elderly father died, a child went to college for the first time, a husband diagnosed with MS, surgery on a cancerous tumor or chronic depression or fibromayalsia. Her organizational skills were unmatched and she ran the Deacon Board like a swiss watch – until she was diagnosed with ALS, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. She was devastated; we were devastated. She and her husband lived on a dead end in Hillsborough, just across the canal from church. She escorted me to their glass enclosed patio – clearly her favorite room in the house. She sat on the couch and I sat in the flowered chair opposite her. We were surrounded by 30 plants that she had tended with her own hands. The feeble, shaky hands that now produce horrible penmanship. She had a list beside her that read: tomatoes garlic book group Beth - why me pills “Jean, how are you?” She began to cry and that was the end of our conversation. I moved to sit beside her on the couch and held her hand while she cried. Occasionally, she would look out the window, attempt to fight back tears and find words. But the tears won. Instead she would reach for another tissue as I squeezed her hand tighter or rubbed her back. From the ALS Association's website: She fed her body with the best organic produce. She exercised religiously. She prayed vigorously. She read voraciously. And yet her body is no longer nourishing her muscles. Beginning with her hands and now that I'm holding one in mine, I can feel the lack of form between her thumb and forefinger. I began to cry too. I can still feel the pain of those 45 minutes together. Not physical pain yet, just raw pain. Pain without words, pain of finding yourself so small in relationship to something so devastating. Pain of life lost too soon. Pain that makes talking about "why me?" unrealistic.

"Well," she said, "I'm going to start dinner now." I kissed her lightly on her forehead and said I'd see her on Sunday. “I love you Jean.” “I love you too,” she said slowly with her signature raspy voice. |

What is this blog about?These are some of the reflections that I am fashioning into a memoir about coming to peace with my husband's diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

|